"I Want a Game with Many Winners": A Conversation with Brewster Kahle

Brewster Kahle is the founder and director of the Internet Archive--an independent library with the admirable goals of (1) preserving the Web and all printed texts and (2) making them freely available. 2021 is the 25th anniversary of the launching of the Internet Archive. This conversation was recorded via Zoom with Kahle in San Francisco, CA, and Butler in Northport, AL, July 2021. It has been lightly edited, mostly for grammatical reasons.

A video of the conversation is available on the Internet Archive.

KAHLE: Jeremy!

BUTLER: Brewster, so nice to meet you.

KAHLE: Good to meet you. And I just wanted to say thank you very much for the positive reception on our microfilm project.

BUTLER: Certainly, I'm a big fan of the Internet Archive and have been for years. Maybe you could fill me in a little bit more about what this microfilm project is?

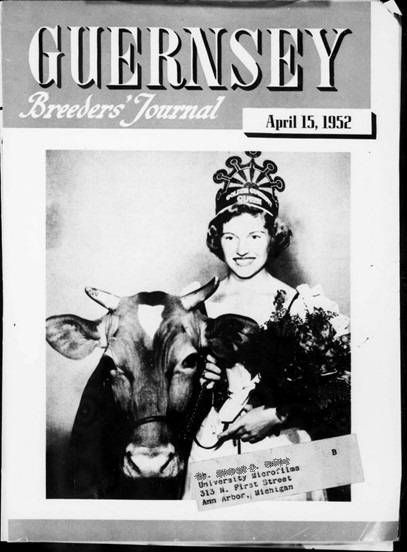

KAHLE: What we're doing is receiving [microfilm], working on the digitization process, and then reaching out to individual publishers to see if we can put the whole thing up. How should we make things accessible? Certainly the public domain, we will give all that away. And then there's... What's the right way for other things? There's interlibrary loan. There's blind and dyslexic. There's machine learning. There's potential for controlled digital lending [CDL]. What are the right ways to go? We're reaching out to some of the publishers, like the Guernsey cow folks.

BUTLER: Guernsey cows has a publication?

KAHLE: It's not for the cows to read.

BUTLER: We think!

KAHLE: Yes, we think! But yes, it's one hundred years of the Guernsey cow. I should share this.

KAHLE: Yes, here it is [Guernsey Breeders' Journal]. She just made my day. It was, like, we're doing something right here.

BUTLER: I'm a fan of old texts. Just in general. But I'm particularly a fan of the Internet Archive's collection of genealogical material from around 1910 and earlier, because there's all these enormous, big, fat genealogies that were published back in those days. For an amateur genealogist like me they are a treasure trove.

The reason you reached out to me was because of Jump Cut, which is this journal that started in 1974 with three editors, only one of whom is still alive, Julia Lesage. They've never accepted advertisement advertising. They've never had a publisher. They've never had an institutional affiliation. And so she was really desperate to try to find some place to store all of this material from Jump Cut. And so I suggested the Internet Archive as being a great fit. And what's really cool about your new microfilm project is that your versions of it are much better than the ones she had. Because what she did for the first 43 print issues is she scanned them, but they're in an odd shape, they're kind of a... They printed them on tabloid paper and they're sort of newspaper size, so she only included the text [which had been OCRed]. She didn't include any of the images and it has none of the formatting of the original...

KAHLE: Which is so important.

BUTLER: Right. And so when I looked at the microfilm version, I was really pleasantly surprised at how well the images reproduced, because you never know with microfilm.

KAHLE: It's black and white or grayscale. And sometimes the contrasts can be... They could have filmed it with high contrast to really emphasize the text.

BUTLER: I was very pleasantly surprised at how good it looks. For the first 43 issues your version of it is really quite superior to what Julia had. And then Jump Cut made the transition to it being all online in 2001 and they stopped doing the print version. All of the post-2001 online issues have been downloaded as PDFs and then uploaded to a collection on the Internet Archive. A lot of it is already in the Wayback Machine, but...

KAHLE: It's surfacing it in those collections that is important. I was just so delighted to go and find your contribution in the Internet Archive.

BUTLER: Julia's attitude has always been, as she puts it, "Don't be stingy." They've always tried to distribute Jump Cut as broadly as possible and at as low cost as possible.

I don't know where this interview might wind up. I retired last summer and one of the things I pledged is I would never write another word of academic prose. So I don't really know what'll happen with this interview. But assuming that it might wind up in Jump Cut, what I'd like to talk about first would be your initiative to scan both texts and films. Didn't you absorb Rick Prelinger's archive?

KAHLE: We actively support it. He's on our board.

BUTLER: I reached out to Rick about, gosh, must be 30 years ago now because the University of Alabama, where I taught, had hundreds of 16 mm short films, educational films that they used to rent out to schools around the state. So this would be stuff like How to Brush Your Teeth and Duck and Cover. And you have a beautiful compete short with Disney animation of The Story of Menstruation. So we had all these all these films. And, of course, at that time they were moving everything to videotape and they were about to throw them into the dumpster. So I stopped them and I reached out to Rick and said, is this something that the Prelinger Archives would be interested in? And he said, yeah, great. And so he sent out a truck and took all of these prints with them. So I would assume, actually, that some of those 16mm films...

KAHLE: A lot of those are been digitally digitized and put up on the Archive. And a lot of things from that era of his collection ended up at the Library of Congress.

BUTLER: Do you have any ongoing relationship with the Library of Congress?

KAHLE: Absolutely.

BUTLER: So how does that work?

KAHLE: We collect the Web for them, is the biggest thing right now. We used to digitize books inside the Adams Building, which was exciting. Actually, [the Librarian of Congress] Carla Hayden asked me to be on a committee to help modernize the copyright office, which could use it. You know, they're the big boy in our in our area.

BUTLER: I saw a little video clip of you on your Wikipedia article where you were giving a little tour of your scanning center. And the thing that piqued my curiosity the most about that was somebody was scanning a film that looked like a 16mm film, but it was a home movie. Is this an ongoing initiative of the Internet Archive? Do you want people to send you physical copies of home movies?

KAHLE: Yes. I take the lead from Rick Prelinger in this type of area. I had never heard of "ephemeral films" before meeting Prelinger and understanding how important they are for explaining the 20th century. And then when he said, "OK, I'm really going to go into home movies...." Again, I just thought, you're crazy. I think of home movies as those things that your parents did after coming home from a trip. They pull out the screen, turn off the lights, and it's boring to watch your own family, much less somebody else's family's home movies. But then Rick said, no, no, no, it's going to be important. And he did these "Lost Landscapes" series. These are all from home movies of, say, San Francisco, and he's on his 12th year. They sell out the Castro Theater, the largest theater in San Francisco, six months ahead of time in a couple of days.

BUTLER: Wow!

KAHLE: The overflow crowd comes to the Internet archive. That's seven hundred people. If you cut it and contextualize it... Well, actually, he doesn't even really contextualize. He just cuts it and he just puts it up and then people react. Having this experience of watching a movie in a community is something! It's like talking loud in a library. You're not allowed to do that! So he encourages people to call back to the screen and say, "I know what that is! That's this particular corner!" And so he leverages the group to make it an event. It's a film showing as an event. It's brilliant. And he's gone on to do this in many different cities. He recommends that people film bus stations and gas stations and supermarkets and not just birthday parties and zoo visits.

BUTLER: My grandfather was quite the amateur filmmaker. He was born in 1900 and died in 1965. He was a teacher and he saw every family trip as an opportunity for education. He shot have all sorts of things. He shot the Dionne quintuplets, in Canada. But all it is, is this is very far away shot of a chain link fence and you can see a house in the distance. He also shot footage of FDR when he came to North Dakota, those kind of things. So there are these hidden nuggets within home movies.

KAHLE: The new ones are things that we're doing on our phones. And people are trying to figure out what do they do with those. Some of those get posted on YouTube. YouTube writ large is too big for us, but we try to find the important pieces of YouTube, as evidenced by them being cited in tweets or on the Web, or that librarians say are important. So parts of YouTube, but then that's not getting your family's videos and photos. I'm not sure how much people even relook at their phones' collections. And then those phones die and I think with it goes our family histories.

BUTLER: My next question would be related to that because, I taught filmmaking when I first started out and I have many friends who teach filmmaking, so is the Internet Archive accepting, say, student films or student projects or...

KAHLE: Go to archive.org and in the upper right there's a button says "upload."

BUTLER: So you don't want the physical copies, though?

KAHLE: We're all digital now, right?

BUTLER: I'm talking about 8mm or Super8 films from the '70s and '80s.

KAHLE: Oh yeah. We want we want all those.

BUTLER: Is the Internet Archive ever going to run out of space?

KAHLE: Physical or digital?

BUTLER: I'm interested in both.

KAHLE: Let's take digital. The Internet Archive has got about 70 petabytes of data, stored in multiple locations and spinning on disk. And given the support levels that we have now from end users, donations, and foundations and libraries, we can keep up. We can continue growing. But we do make decisions. We don't collect all of YouTube. When people are posting 24 hour baby cams, this is not going to happen. But text is small, right? There's only seven billion people that can only be typing 60 words a minute, 24 hours a day. So I think we're OK on text. Images, videos come larger. It will really depend on support. And are we relevant? Physically, we started collecting materials a decade ago or more. We're now twenty five years old this year.

BUTLER: Congratulations.

KAHLE: Thank you. So I guess 15 years ago maybe, we would start collecting physical materials and trying to learn how to do that well. Because we see the digital version is the access version, our preservation version can be very dense. And not very accessible. Yes, we know where it is, but we think of it as a preservation function. But we're up to our third warehouse that we've converted into a physical archive to cost-effectively store these materials because libraries are deaccessioning their physical collections at a velocity because digital is so much easier to access with added affordances and search, and you don't have to physically go there, and all sorts of things. That natural transition is on right now. We encourage people to not deaccession and use our technologies for storage. But if they're going to deaccession, deaccession to us. We get several requests a day, or several offers a day, not all of them come through, to take over collections from libraries and individuals. 78 RPM records is a big interest for us.

BUTLER: They're difficult to store. I mean, they're fragile.

KAHLE: If you don't drop them...

BUTLER: They're brittle.

KAHLE: They are brittle. Don't drop them. But they're going to last centuries. These things are hardy, but they only last centuries if we don't throw them away, like microfilm. Microfilm, I don't know who came up with the number, it'll last for five hundred years. Unless you throw it away. And so we're trying to collect one physical copy of everything ever published.

BUTLER: Wow.

KAHLE: We're not really interested in duplicates unless there's some real reason. And so, one copy of all books, music, video. In physical form.

BUTLER: Wow. That's very intriguing to me, because, as I mentioned, I retired last summer and so I need to find a new home for my entire home library. I think I found a home on campus here at the University of Alabama. But if not, would that be the sort of thing that...

KAHLE: Yes, we get those calls all the time. And what's a lot better is getting that call before people die.

BUTLER: Why?

KAHLE: Because it can be put together to be put away. We try to keep collections whole, which is different from how a lot of places do it. They take things and they distribute it through their physical holdings because their access method is often browsing the stacks. We don't have that. I think some of the interesting nature of what it is we have will be less the individual objects and more the collections.

BUTLER: Interesting.

KAHLE: So when we digitize, we go and keep things in collections so it can be your collection of books and other materials around your subject area. That I think will be more and more what is interesting to future scholars.

BUTLER: I'll spread the word because there are a lot of my contemporaries who are retiring now. And like me, they really don't plan to do academic research in the future. The Tuscaloosa Public Library doesn't want my books. And it's funny, I have long runs of academic journals. Nobody wants those. [Kahle raises his hand.] I'm afraid it's a little too late for most of them. I gave a long run of Screen to Rick Prelinger.

KAHLE: That's something he would love. So we are now, as you know with Jump Cut, our anchor of our periodical collection is based on microfilm collections, and now we're starting to receive donations of... We want complete runs, if at all possible, or at least long runs, but we're getting them by the shipping container now. That's good because they're just being dispensed. We want them and then we're trying to actively collect everything we can from online in the Wayback Machine. And now we have scholar.archive.org that's really focused on open access to resources that aren't naturally in other preservation programs.

BUTLER: I just recently found scholar.archive.org, which I guess is kind of in beta.

KAHLE: Yeah, that's still new.

BUTLER: Can you describe that a little bit more for me? Because like I say, I just found out about it yesterday, I'm not really clear on its purpose.

KAHLE: Yeah, it's two components. It's attempting to pull together articles, information about articles that we don't have and things that are in the Wayback Machine and point to them. The Wayback Machine is so large that it's hard for people to move through it. So this is an index into the Wayback Machine and it also helps guide our collecting practices. When we discover new URLs [Website addresses], we will know if we already have it. It's not a competitor for Google Scholar, but it has a lot of things that Google scholar doesn't have yet. We hope to integrate these collections into Google Scholar because they've got so much more traffic than we do.

BUTLER: So I know there's some almost competitive stuff going on between you and Google's scanning projects, but you also are cooperating in certain ways or not?

KAHLE: They have scanned so much more than we have in terms of their library project, but they're not very available.

KAHLE: I don't have a institutional subscription to Hathi Trust. So how do we get access to these things? It's really good for the elites that are in high-end colleges that can afford those, but what about the rest of us? So, I commend what Google has scanned and done, but I'd at least like to see the public domain be publicly accessible.

BUTLER: I don't get that. And it's frustrating. You go look up some 1910 book and all you get is a limited preview, if that.

KAHLE: They got sued for years and years and years from the Authors Guild and the publishers. Years! I don't know how many tens of millions of dollars they spent on that—just on the lawsuit. That's not good. But we do like working with Google whenever we can and we hope to work with Scholar more.